An Altar for Our Ashes

灰燼之壇

An Altar for Our Ashes is a traveling altar offering sacred grounding and collective rituals for these times of unraveling.

This project emerges from two decades of working for dignity and justice. From Afghanistan to Zimbabwe, I witnessed how spiritual practice activates faith, unites communities, and helps birth new worlds.

Rooted in Taoist cosmology—where heaven, earth, and human are interwoven—and shaped by traditions of reverence across cultures, An Altar for Our Ashes evolves with each activation, welcoming offerings from the communities it meets. Participants are invited to:

TRANSMUTE: Offer grief and intention to fire: names of loved ones, losses, hopes for the future. Flame transforms them, with ash holding what must be remembered and smoke carrying what longs to rise.

DIVINE: Seek guidance using 筊杯 (bwa-bwei, moon-shaped divination blocks). Questions and responses are recorded, forming a growing archive of communal wisdom. Later, they are remixed into new divination sticks, offering poetic insight rooted in collective experience.

OFFER & RECEIVE: Contribute to the altar’s living ecology—via notes, photos, talismans—and take something in return. Each act of giving and receiving deepens a circuit of care, reminding us grief and hope are never carried alone.

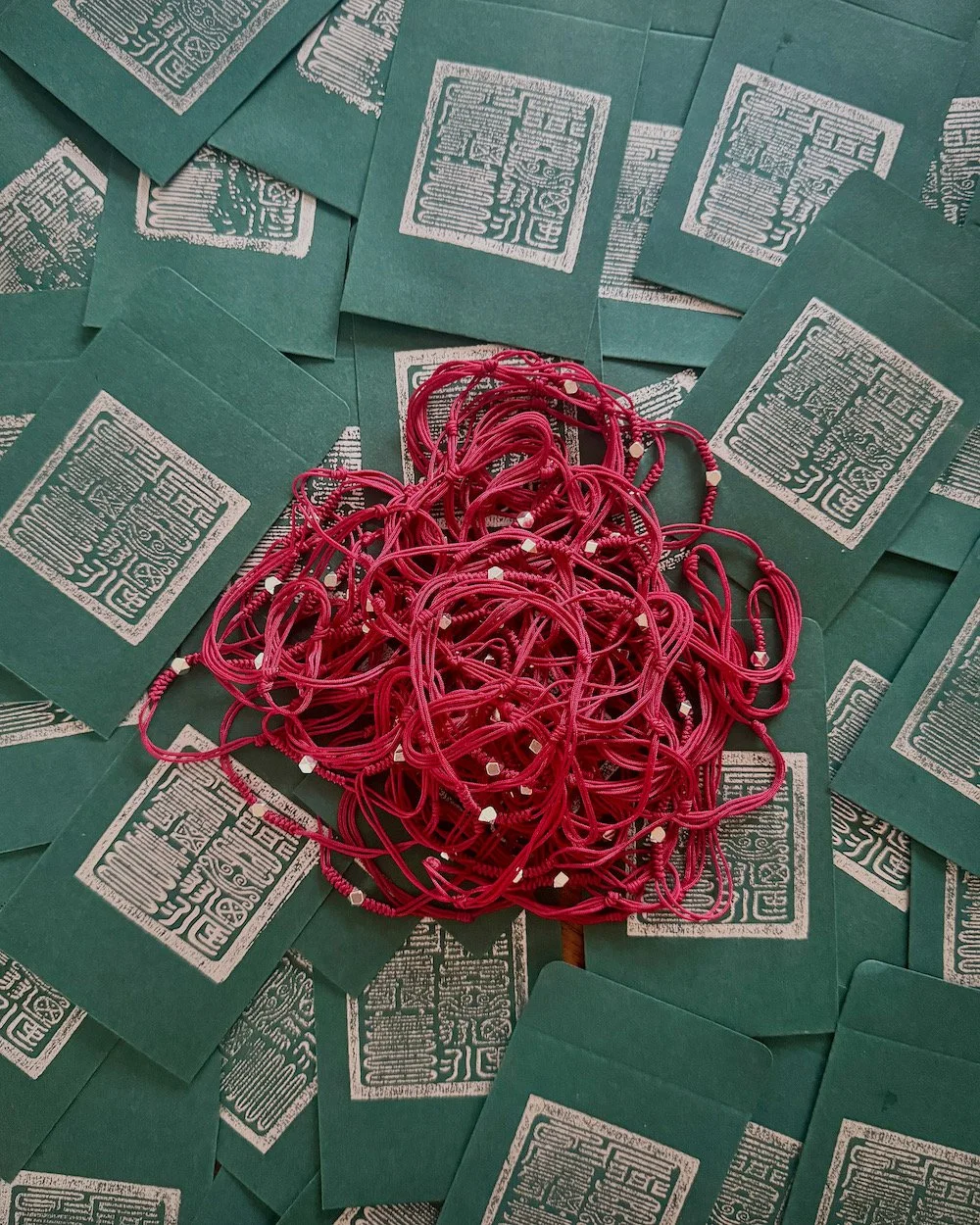

After their ritual, each participant receives a bracelet on their wrist, to bring protection and good fortune. In East Asian folklore, it recalls 月下老人 (yuèxià lǎorén, the Old Man of the Moon), who ties a red thread around those fated to meet. Here, it becomes a thread of the collective, connecting you to every spirit who has bowed, prayed, and offered at this altar.In Buddhist traditions, 緣分 (yuánfèn) speaks of karmic affinity, the invisible ties that weave across lifetimes to return us to one another.

Its journey began in São Paulo, Brazil in September 2025; soon, it will continue on to Vientiane, Laos, then to gatherings for social and climate justice, carrying gestures of care across lands and movements.

Over time, I hope to create an online map tracing the altar’s global journeys and an open-source guide for others to create altars in their own traditions. As altars multiply, they will form a distributed ritual ecology: rooted in ancestral wisdom, attuned to the ruptures of today, and committed to our collective fight for life.